Fidèle's story

My name is Fidèle Deholo. I’m 19 years old, and I come from Cameroon. I’ve been in Italy for over two years now. I live in Messina, in a First Reception Centre called the Grand Liberty Hotel.

follow Fidèle's journey

click hereHome

image source: Google maps

Editor’s note: The following story is based on conversations with Fidèle from April 2019. It reflects his views and life at the time, much of which has changed since. The text was edited and collaboratively re-written for clarity with his complete involvement and approval. Most importantly, this remains his story, told in his words.

My name is Fidèle Deholo. I’m 19 years old, and I come from Cameroon. I’ve been in Italy for over two years now. I live in Messina, in a First Reception Centre called the Grand Liberty Hotel.

I speak three Cameroonian languages and four European ones: Douala, Bamiléké and Ewondo, Italian, French, English and some Spanish. At school in Cameroon, we spoke French, but we spoke a mix of French and English called Francanglais in the street.

I was born and raised in Douala, the economic capital of Cameroon. My father worked in a lumber factory, and my mother owned a restaurant. We were six children: three sisters and three brothers – of which I’m the youngest. One of my older brothers is currently in Morocco, trying to enter Spain and my three sisters are still in Cameroon with my mother.

I come from a suburb called Nyala that’s rife with violence, poverty and delinquency; over there, the strong dominate the weak. It’s not an easy life.

I come from a suburb called Nyala, rife with violence, poverty and delinquency, where the strong dominates the weak.

My father died when I was 6 or 7 years old. That’s when my relationship with my family began to fall apart. I stopped listening to my mother and started arguing, disrespecting and disobeying her.

By the age of 11 to 12, I started spending most of my time in the streets, hanging out with older kids from the neighbourhood. We would spend our days either at the football stadium, in the street or at parties, having fun, living day-to-day. Poor and disillusioned, we didn’t bother to think about the future, only the moment we were in.

Neighbourhood rivalries often turned violent for a litany of reasons; competing football teams, girls’ attention, ethnic rivalries, drug deals. We couldn’t even go to a nearby community without getting jumped.

Eventually, I spent more time on the street than with my family. Sometimes, I would leave the house for two or three days at a time.

I dropped out of school at age 10. My mother begged me to start studying again, but I wouldn’t hear it. I didn’t like rules or being told what to do; I wanted to be free of constraints. Today’s Cameroonian youth feels lost. We’d see university graduates struggle to find work, so we thought “what hope is there for us?” As a result, 80% of the kids in Nyala would take to the streets. In hindsight, I think I made a mistake.

Today's Cameroonian youth feels lost. We’d see university graduates struggle to find work, so we thought, “what hope is there for us?” As a result, 80% of the kids in Nyala would take to the streets.

At the age of 8, my mom gave me a laptop for Christmas. It was small with a pig’s head on the lid. It was basic, but it could handle a few games. That’s how I first developed a love for computers. When I dropped out of school, I told my mother that I wanted to train as a computer repair technician. That way, at least, once I had finished my studies, I could find a job – instead of struggling with a useless diploma. So, I took IT classes from the age of 10 to 12.

In 2014, my big brother died in a gang fight between two rival neighbourhoods. My family was devastated and I felt somehow responsible for taking part in that lifestyle. It opened my eyes to what I was doing with my life. I realized that it wasn’t how I wanted to live. Two months later, I secretly left Douala for northern Cameroon – without telling my mother.

Journey

FOTOKOL, CAMEROON

I joined my grandfather in Fotokol, my dad’s hometown. When I arrived, he told me, “Now that you’ve become a boy, if you want to stay here, you’ll have to earn your keep.” I felt better in Fotokol, at peace. I would help my grandfather herd cattle. Every day, I would eat breakfast, wrangle the cows, and walk 25 to 40 kilometres to feed them. I stayed there from December to February 2015. It was much quieter than in Douala; there wasn’t much crime or violence. Until the attack.

On February 4 and 5 2015, Boko Haram attacked our village. They started killing everyone, setting houses on fire. I managed to hide until the police arrived to rescue us, but had lost my grandfather in the chaos of it all. I haven’t heard from him since.

I tried calling my family in Douala, but no one picked up, so I told myself that they’d forgotten me.

I took a train for Yaoundé, the capital. It was rash. I’m not even sure what I was thinking.

On the train, I met a young aventurier on his way to Equatorial Guinea. Aventuriers (or adventurers) are what you would call migrants, those who leave their countries and risk everything in search of a better life. I told him my story and what I had been through: my problems, my brother’s death, and all that. He asked me to join him. I had just turned 15.

MALABO, EQUATORIAL GUINEA

image source: Google maps

When we reached Malabo, he took me to a friend’s house, who helped me find a job washing cars. Eventually, I paid back what I owed my friend for the trip and even managed to put some money aside. At the time, I wasn’t thinking of going to Europe; I didn’t even know it was possible, as our newspapers don’t really cover it. After three or four months, local police caught me and asked for my visa. I was undocumented, so they gave had 15 days to leave the country. That’s when I decided to go to Nigeria.

To reach Nigeria, I first had to return to Cameroon and cross through the English-speaking region at the Nigerian border. Since I had no papers and couldn’t travel via the regular route at the border, a friend suggested I take a smuggling boat. I paid 67,000 CFA francs (120 USD) to a trafficker. We left under cover of night, around 10:00 p.m., with no more than 15 people onboard. Our boatsman carefully avoided the coastguard, and the trip lasted something like 45 minutes.

NIGERIA

image source: Google maps

Nigeria was difficult at first. I found myself in a village called Oron, in Akwa Ibom state. I didn’t know anyone or speak the language, but with my francanglais – a mix of English and French that we speak in the streets in Douala – and the little pidgin I had learned in Cameroon, I started to get by in English. I was already a street kid, so I had no problem sleeping outside on a cardboard box. What mattered most was my state of mind; I had to always stay positive, telling myself over and over again, “It’s going to be okay. It’s going to be okay. It’s going to be okay.”

When I first arrived at the Oron bus station, I didn’t know what to do or where to sleep, so I just wandered around aimlessly. This man, a luggage handler at the station, approached me and asked what I was doing there and where I was from. I told him everything, and he kindly took me in. He offered me clothes, a place to stay, some food. Two days later, I started working with him at the station, loading suitcases onto departing buses. I’ll always be grateful to that kind man. Without him, I don’t think I would be here today.

I'll always be grateful to that kind man. Without him, I don't think I would be here today.

Later on, he introduced me to a Cameroonian woman who sold clothes. “Son, you chose to leave your country, so you now have to work for a living”. I started selling water for her, and eventually, clothes. After some time, I met a young Nigerian man who convinced me to break off with him and start importing clothes from Benin to sell in Nigeria.

In Benin, goods tend to be cheaper than elsewhere in Africa because it's the port of entry for lots of clothing, telephones, and other stuff.

In Benin, goods tend to be cheaper than elsewhere in Africa because it’s the port of entry for lots of clothing, telephones, and other stuff. Since he didn’t speak French very well, I would take care of the shopping in Benin, and he would carry them across the border because he didn’t have to pay duty. It was in Benin that I first saw migrants leaving for Europe.

But at some point, he started to change; his behaviour, his way of speaking. Growing up in the streets, I learned how to read people, and I soon realized that I could no longer trust him. Every time we’d split the money, his phone would ring, and he would answer in a language I didn’t understand, speaking to someone I didn’t know. I grew suspicious. I began to worry that he would one day take my share and leave me with dangerous people. I decided that what little money I had made was enough and that it was time for me to move on.

In Lagos, I met a Cameroonian man who lived in Algeria.

In Lagos, I met a Cameroonian man who lived in Algeria, and we added each other on Facebook. Once he’d returned, he’d often write to me, suggesting that I join him. “If you work in Algeria, you’ll easily find a place to stay. Don’t worry about documents; there’s always a way to get by without them.” I decided to see for myself.

At the time, I didn’t know anything about the route, so my friend introduced me to a smuggler who could get me to Niamey, in Niger. The man took me to the bus station and found a driver who, in exchange for 45,000 CFA francs (around 85 USD), would take me across the border as his motor boy – his apprentice. All I had to do was take care of the passengers’ luggage until Niamey.

My friend warned me about the journey. “Brother, there’s a lot of police on the road. If they catch you without any documents, they’ll throw you in a cell and take everything they find on you, so it’s best to pay for your trip in advance and hide whatever money you keep on you”. Following his advice, I hid whatever money I had in my shoes and pants, even tearing some of the lining of my clothes to create hidden pockets.

"Brother, there's a lot of police on the road. If they catch you without any documents, they'll throw you in a cell and take everything they find on you, so it's best to pay for your trip in advance and hide whatever money you keep on you"

NIGER

image source: Google maps

Once in Niamey, I was on my own; it was up to me to find a way to Algeria.

After searching for two days at the train station, I finally found a smuggler who would take me to In Guezzan, in Algeria. We left Niamey, and he took me to Arlit, near the Algerian border, where I waited a month for the next driver to arrive. All I could do there was eat, sleep and wait. It was deathly hot, so we didn’t go out much.

The caravan arrived a month later, and we left for the desert.

We were 15 people in the back of a pick-up truck, stacked into four rows. When I was told that all of us had to climb in, I didn't understand how we’d all fit. But they somehow packed us in, and we left.

There was so much sand and dust in the desert that they gave us masks and scarves to protect us. Typically, the journey from Arlit to In Guezzan would take 7 to 8 hours, but we had to avoid border patrols in the desert, so it took us over three days. We would drive for a bit, stop somewhere, climb down and wait until the patrol had left the area. By the third day, we had run out of water.

A single smuggler won't take you all the way from Niger to wherever you want to go; the route consists of a network of drivers, each managing a specific portion. A driver will take you to a designated location, where another driver will pick you up and take you to the next, and so on.

Our drivers were all Algerian Tuaregs; they pretty much have a monopoly on smuggling people between Niger and Algeria. They’re heartless. They aren’t concerned about our well-being or health. We’re just a commodity for them; only our money matters.

IN GUEZZAN, ALGERIA

image source: Google maps

On the evening of our fourth day, our smuggler stopped in the middle of the desert, yelling, "Yallah! Yallah! All of you get off!".

“You see the red light, there? That’s In Guezzan. A military encampment surrounds the town, but they won’t intervene once you’re inside.” He then gave us a guide, a local teenager – maybe 16 or 17 years old – who would sneak us into the city. Under cover of night, we walked for two hours until we reached the red light of the military encampment. The boy led us through a hole in the camp fence, and we finally entered the town.

In all, I spent four to five months in Algeria.

Next, I travelled to Tamanrasset.

TAMANRASSET, ALGERIA

image source: Google maps

In Tamanrasset, there was a busy intersection called Chad Square where migrants would wait for work as day labourers. When bricklayers had finished a building, they needed someone to clean the cement and debris on the ground, so they would hire us for about 2000 to 2500 dinars – a rather decent pay. And since we were so vulnerable as undocumented workers, robbers would often target us. It would happen often that on paydays, a couple of them would show up on a motorcycle, pull out their knives and steal our money.

Later, when I was in Oran, a Burkinabe and a Guinean were stabbed to death because they refused to hand over what they had. What's worse, we’d have no way to denounce them or defend ourselves.

The migrant ghettos in Tamanrasset are run by Africans who either married a local woman or opened a successful business in Algeria. They would buy apartments and rent them out for about 1000 dinars a week per person. A room could hold ten or eleven people, so a three-bedroom apartment with a living room could accommodate fifty Africans. It was cramped and uncomfortable, but at least we weren’t sleeping on the street.

One day, rumours began to circulate about the local Tuareg planning to kill all the migrant workers. Riots erupted throughout the city, and groups combed through our neighbourhood, attacking every Black African in sight, and throwing Molotov cocktails into our houses. By the time the violence subsided, they had razed the African ghetto in Tamanrasset to the ground. The hospitals were full of burnt Africans. That’s when I realized that Algeria was not safe. I had to get out.

So, I left for Oran, where I worked for another three months at a construction site.

Fidèle Deholo (16) takes the tram in Oran, Algeria, to reach his job as a cleaner at a construction site. Oran, Algeria, Summer 2016.

image source: FIdèle Deholo

Riots erupted throughout the city, and groups combed through our neighbourhood, attacking every Black African in sight, and throwing Molotov cocktails into our houses.

One day, rumours began to circulate about the local Tuareg planning to kill all the migrant workers. Riots erupted throughout the city, and groups combed through our neighbourhood, attacking every Black African in sight, and throwing Molotov cocktails into our houses. By the time the violence subsided, they had razed the African ghetto in Tamanrasset to the ground. The hospitals were full of burnt Africans. That’s when I realized that Algeria was not safe. I had to get out.

And so, I left for Oran.

ORAN, ALGERIA

image source: Google maps

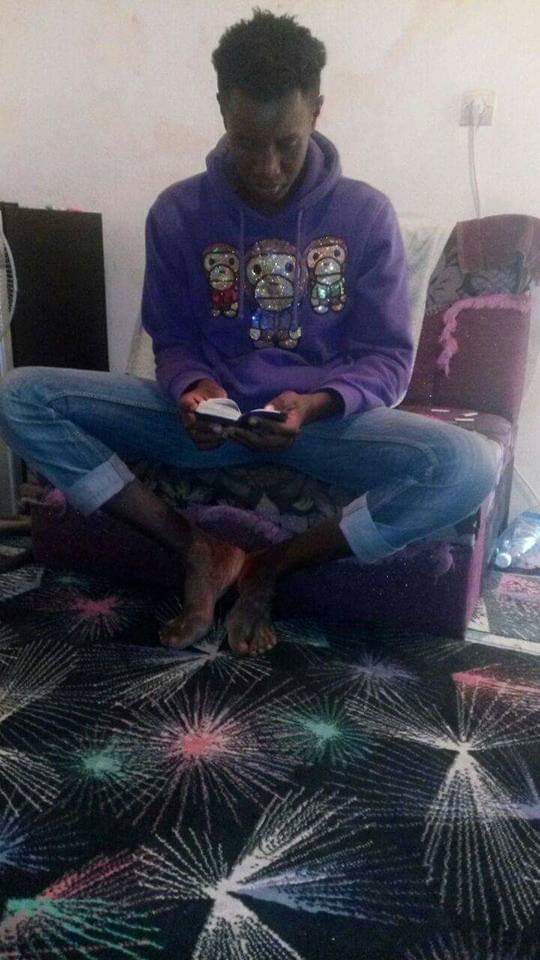

Fidèle Deholo (16) reads in the living room of his apartment in the migrant ghetto in Oran’s Amandiers neighborhood, Algeria, where he lived with 15 other migrant workers for a period of two months. Summer 2016.

image source: FIdèle Deholo

After three months of work on a construction site, it was payday. My boss told us that he had to step out to fetch our money at the bank. I had developed some sort of tooth or gum infection, so my mouth was swollen and sore, and I had decided to rest. A few minutes later, police cars arrived; our boss had betrayed us. I thought my life was over; due to escalating tensions, police had recently started deporting migrants, and if you were caught without documents, they would drop you off in the desert between Algeria and Mali – the equivalent of a death sentence.

I was lying in bed, crying, as two policemen came barging in. When they saw my swollen jaw, they asked me what was wrong. Both spoke French well, so I told them about the infection, and they decided to bring me to a hospital for treatment before sending me back to Tamanrasset, where a patrol would dispatch me to the Malian border.

Thank God one of them had a heart. At the hospital, he deliberately turned away and allowed me to escape. Although he didn’t openly tell me to flee, I’m positive he did it so that I could. I was lucky enough to come across a good person. Despite my infection, he could have easily sent me off to Tamanrasset, but he didn’t.

Once I had escaped the hospital, I went back to the migrant ghetto where I stayed, in a neighbourhood called les Amandiers. I explained to others there that we were all in danger, that the police had caught everyone at my construction site and that they were most likely going to deport them. That’s when I knew that I had to leave Algeria. I had to go to Europe. But first, I had to go through Libya.

For Africans in Algeria, Europe is like El Dorado. We believe that in Europe, all our suffering and problems will be over. We believe that if we reach it, we'll finally be free.

CROSSING THE BORDER

image source: Google maps

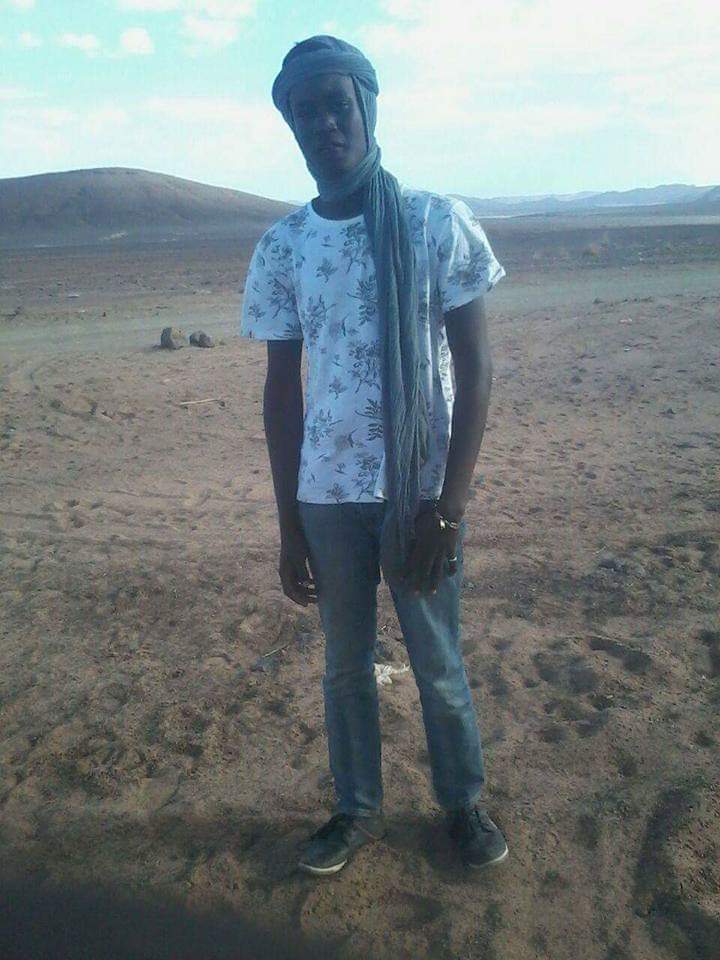

Fidèle Deholo (16) crosses the border into Libya near Debdeb, Algeria in late 2016.

image source: FIdèle Deholo

In Oran, I convinced a friend, I’ll call him J., to join me. We found a trafficker who promised to smuggle us into Libya and then help us cross over to Italy. His guide was in Tamanrasset, though, so we had no choice but to return there. I wasn’t sure I could trust him, but I was exhausted and desperate to leave Algeria, so I gave him all my money. “Here. My life is in your hands.”

The initial plan was for the guide to drive us through the desert border at Debdeb until we reached Sabha, where we could organize our crossing to Europe. But before reaching Debdeb, our smuggler told us to get out of the truck and cross the border on foot; on the other side, another car would await us to continue our journey. Trusting him was a mistake; we crossed, and found no one.

The route being quite popular, we eventually came across another migrant caravan. But they didn’t just bring us to Sabha; they sold us to one of Libya’s worst prisons: Ali Ghetto.

SABHA, LIBYA

image source: Google maps

In Libya, there are two types of prisons: the state prisons and the Asma Boy prisons. The Asma Boys are a loose network of gangs that imprisons and resells migrants throughout the country.

In Libya, there are two types of prisons: the state prisons and the Asma Boy prisons. The Asma Boys are a loose network of gangs that imprisons and resells migrants throughout the country – Ali Ghetto being one of their biggest bases of operations. During the Gadhafi era, it was a state prison similar to those here in Italy. But during the civil war, the government abandoned it and the prisoners escaped, which left Ali – the gangster who had taken over most of Sabha at that point – to take possession of it.

Every Wednesday, the guards would force each prisoner to call their friends or family and ask for a 3,500 Libyan dinar ransom for their release. Since I had paid for my journey in full in Algeria, I desperately tried calling my smuggler in Oran; but his number had been disconnected.

I reluctantly called my family next. They were shocked to hear from me after so long, not to mention given the circumstances I found myself in. My mother explained that she was facing deep financial troubles and couldn’t help me, “We’re not doing too well, son. The amount you’re asking for is a lot”. She would look, but it would take some time.

When we first arrived, J. tried to rebel; he’d tell the guards that he had no money and that they wouldn’t get anything from his family. So they beat him terribly before the calls. Initially, his family didn’t believe that he was in prison, so the guards sent them a video where they gagged him, tied his hands and feet, and burned his body with molten plastic. If his mother didn’t pay, they said, the next video would be of her son’s corpse. And so, she sent the money, and he was released a month before me.

J. is in Bologna now. He still has scars all over his body.

... for two months, they abused, tortured and beat me. I didn't know what to do. I felt beyond helpless.

Eventually, my calls to Cameroon stopped going through. This angered the guards, and for two months, they abused, tortured and beat me. I didn’t know what to do. I felt beyond helpless.

Fortunately, a Nigerian guard from Akwa Ibom patrolled our section, the state where I lived in Nigeria. One day, as I was following him to the phone, I spoke to him in his dialect. “Shut up. You shouldn’t talk”. But I wouldn’t listen; I told him that I had lived in Akwa Ibom and that I knew the area well, and started naming obscure places known only to locals so he would know that I was telling the truth. I told him that I was Cameroonian and that I had no one to help me. Finally, he broke. “We’ll manage until we figure out how to get you out of here.”

Fortunately, a Nigerian guard from Akwa Ibom patrolled our section, the state where I lived in Nigeria. One day, as I was following him to the phone, I spoke to him in his dialect. “Shut up. You shouldn’t talk”. But I wouldn’t listen; I told him that I had lived in Akwa Ibom and that I knew the area well, and started naming obscure places known only to locals so he would know that I was telling the truth. I told him that I was Cameroonian and that I had no one to help me. Finally, he broke. “We’ll manage until we figure out how to get you out of here.”

From then on, the beatings and ransom calls stopped. On the days when Ali came to log the prisoners’ calls, we would have to line up so that he could speak to us one by one. Since Ali just wanted a broad account of whose ransom to expect and who had yet to pay, he never stayed long enough to reach those at the back of the line – which is exactly where this guard would put me every time.

I tried my best to appeal to the guard’s feelings of pity, so I lied to him, saying that I had no family left and that they’d never obtain a ransom for me, that I no longer wanted to suffer, that all he had to do was get it over with: tell Ali, and kill me. But he cared for me, and one Saturday night, he helped me escape.

A convoy of trucks had arrived from Niger after more than a week and a half in the desert. They had run out of water, and all the passengers were thirsty and exhausted; so, the guards sent two men to the nearby well.

When the door opened, the guard allowed me to slip out: “Now you can go anywhere. Please, just leave the city.” A taxi was waiting for me outside. The guard wished me good luck and handed me 45 dinars. I couldn’t thank him enough. If I had been caught or if Ali had found out that he had helped me escape, he would have been executed. Today, he’s is in prison in Catania, Italy, because the authorities here found out about his past.

Fidèle Deholo (16) hides in the Cameroonian Ghetto in Sabha after escaping Ali Ghetto prison, where migrants are ransomed to their families in their home countries. Sabha, Libya, late 2016.

image source: FIdèle Deholo

The taxi left me in Sabha, where I convinced someone to lend me a phone with which I was able to contact J. on Facebook. A few hours later, I joined him at the Cameroonian Ghetto and we planned our journey to Italy.

We had to reach Sabratha, where the boats depart for Europe.

At first, I hesitated to call my family. I didn’t want to burden my mother any more than I already had, but I realized that I had no choice. I told her: “Mama, I need your help to go to Italy.” Though it was difficult, she gathered 300,000 CFA francs (around USD 500) to pay for my crossing.

We weren’t alone in the ghetto; with us were other migrants we had met on route to Libya or befriended in Ali Ghetto. Other than J., one of my closest friends was an Ivorian boy; we had bonded on the way to Sabha and had quickly become inseparable in Ali Ghetto. He would often tell me about his past, his aspirations, plans and hopes for the future. His elder brother had already crossed, and once reunited, they would build a new life together.

He would die soon.

ONTO SABRATHA

image source: Google maps

Typically, the journey from Sabha to Sabratha takes two days; however, the road is highly patrolled, so migrants must resort to smuggling caravans, which prolongs it to about a week.

Fidèle Deholo (16) takes a pit stop while travelling from Sabha to Sabratah, Libya, a popular point of departure for Mediterranean crossings to Italy. Late 2016.

image source: FIdèle Deholo

Fidèle Deholo (16) buys snacks at a convenience store en route for Sabratah, Libya, a popular point of departure for Mediterranean crossings to Italy. Late 2016.

image source: FIdèle Deholo

At some point, we stopped at some kind of bunker to rest and avoid Libyan patrols. As teens do, we’d often joke around, tease and insult each other. After more than 3 hours of waiting, we all stepped out for a meal before continuing to Sabratha. My Ivorian friend jokingly made a rude gesture to someone behind one of the smugglers, but the man believed that he had meant it for him and started shouting.

Then we heard a gunshot, and everyone threw themselves to the ground. As everyone pressed their faces into the dust and avoided looking up, I could see my friend’s body nearby, his blood pooling into the sand around him.

Gamz! Gamz! Gamz! [Lie down! Lie Down! Lie down!]”. My friend didn’t speak Arabic, so he didn’t understand why the trafficker was yelling and just kneeled down, frightened and confused. Though none of us completely understood either, we quickly realized that he was threatening to shoot him. We begged him for forgiveness, “Asma malish! Malish!”. “KOULA JAMA GAMZ! KOULA JAMA GAMZ!” (“Faces down! Faces down!”). Then we heard a gunshot, and everyone threw themselves to the ground. As everyone pressed their faces into the dust and avoided looking up, I could see my friend’s body nearby, his blood pooling into the sand around him.

It hurt to see him there, dead, in the dirt, for barely any reason at all. I still don’t know what he did to provoke it.

And so, we left him there and moved onto Sabratha.

On the way to Europe, the slightest mistake can mean death. The smugglers have no mercy.

THE FIRST CROSSING

I made my first attempt to reach Europe on December 14, 2016. It was two days after my birthday.

When we arrived on the waterfront, the sea was agitated. J. refused to leave. He thought the winter weather was too dangerous and told me that he preferred to cross in February or March when the waters would be calmer. I decided to try my luck. I boarded an inflatable boat with 137 people, and we left the Libyan coast at around 23:00.

At about 3:00 a.m., our boat capsized. I remembered seeing two large jerrycans of gasoline, so as soon as I fell in the water, my first instinct was to look for those. I managed to find one to cling to. As everyone was struggling to stay afloat, I wanted to help two or three people, but when I saw so many coming towards me, I realized that my can couldn’t hold them all. I would have drowned. So, I swam away.

As everyone was struggling to stay afloat, I wanted to help two or three people, but when I saw so many coming towards me, I realized that my can couldn't hold them all. I would have drowned. So, I swam away.

At around 8:00 a.m., the Libyan police arrived. Some had found planks, and two people caught the other jerrycan, but out of 137 people, only 15 of us survived. The police fished us out and brought us to the state prison in Sabratha.

When we had reached the prison at around 11:00, our helmsman, one of the few survivors, contacted the trafficker who had sent us to sea, a Libyan man named Moustapha. By 20:00 – 20:30, he’d arrived. He convinced the police to release us, and took us back to his safehouse to discuss what had happened.

I was desperate. I had survived, but I couldn’t afford a second trip. The little my mother was able to send me had served no purpose. I couldn’t ask her a second time.

Thank God for J. His crossing had already been paid for, but he called his mother again and somehow convinced her to cover my fee. Three weeks later, on January 12, a new boat was ready to leave for Italy. Again, my friend wanted to wait, this time for the calmer summer waters, but I convinced him otherwise. “In Libya, morning, noon, and night, bullets fly above our heads. Brother, instead of risking death here every day, we should risk it once while trying to reach Italy. Whatever happens, our suffering will be over.” He paused, then answered, “Till the end, brother.” I’ll never forget those words.

THE SECOND CROSSING

And so, for the second time, I took to the sea. The waters were awful, even more turbulent than before, and I was still traumatized by the shipwreck, constantly terrified that the boat could capsize at any moment.

But this time, we had an excellent helmsman. He told us, “Either we all die, or we arrive in Italy, so everybody calm down and let me handle this. I promise we’re going to make it.” Some cried and begged him to head back, but he refused. “Do you want to go back and die by the gun? We’re about to reach a place where we can be free and happy. In Libya, only suffering awaits.” He knew how to talk to people, how to give them hope.

When we reached international waters, we called for help on the satellite phone that the smugglers had given us. Scrambled German voices responded, and after 30 minutes to an hour, a helicopter spotted us. Shortly afterwards, two small JAC boats arrived to survey the condition of our ship. When I saw them, I thanked God: I was finally safe.

They gave us life jackets and transported us to a large NGO rescue vessel, the Aquarius, run by SOS Mediterranée and Médecins sans Frontières. They welcomed us, gave us food and blankets and took us down into the hold of the ship since it was freezing outside. They told us that they were German, but couldn’t take us to their country because we were in Italian waters. So, they called the Italian Coast Guard to take us to Italy.

By God’s grace, I set foot in Italy on January 14, 2017, in Catania.

source: Guardia Costiera Italiana

ITALY

I felt reborn when I set foot in Italy. I was so proud to have made it to a country where human rights were valued and respected. I thought that in Italy, my new life was about to begin. I thought I’d never have anything to fear, ever again. I would never have to face death or relive the horrors of my journey. I thought that my suffering was over. I saw Europe as a place where everyone can speak their mind, free to do as they please. And finally, I had arrived.

I’ve felt guilty ever since the shipwreck, even more so since reaching Italy. Why had the others died, while I had lived? Why did I survive the journey to Italy? How was I different from all the others?

I’ve felt guilty ever since the shipwreck, even more so since reaching Italy. Why had the others died, while I had lived? Why did I survive the journey to Italy? How was I different from all the others? I’ll never know. I can only thank God for protecting me. Without him, I might not be doing this interview. I saw death, I suffered, but I survived. And God helped me stay strong.

In Catania, the police questioned, identified and registered us, after which I was taken to the Don Bosco reception center for minors in Catania. It was a beautiful place with friendly people. Although it’s not always easy to live in a reception centre, the staff did their best to make us feel comfortable. There was a football pitch, some computers, and other entertainment – a bit of everything, really – which isn’t always the case in such places.

I've made many mistakes in my life, but I decided to change when I reached Italy. I made a promise to myself: to work hard and become a better person.

I enrolled in school and started taking Italian classes, as I was determined to speak the language well. I’ve made many mistakes in my life, but I decided to change when I reached Italy. I made a promise to myself: to work hard and become a better person. That’s why I focused on my studies.

We were told that we had to apply for documents with the Italian Asylum Commission and that we would be interviewed about our lives, journeys and reasons for leaving our home countries. This interview – and the Commission – would decide our fates, whether we’d receive humanitarian protection or not.

After spending four or five months at Don Bosco in Catania, I transferred to Messina. The juvenile court here gave me a tutor here, named Carmen Cordero, a lawyer who has helped me enormously, who genuinely involved herself in my life and has done everything possible to help me integrate.

She helped me with everything when I first arrived in Messina; she enrolled me in school, she prepared me for my Commission interview and even accompanied me there. Eight months later, I received two years of humanitarian protection. Today, I have my Terza Media diploma (8th grade), and I’m continuing my studies to specialize in computer science.

Fidèle discusses his upcoming classes with his mathematics and history teachers at the Battisti Foscolo Adult Education Center, where Fidèle is studying to obtain his High School equivalency diploma in order to transition to the Italian school system where he can specialize in computer science.

Fidèle discusses biology homework with his teacher, Milena, in the staff office at the Battisti Foscolo Adult Education Center.

This is when I began to volunteer with a community organization ARCI Thomas Sankara, a local branch of the Italian Association of Leisure and Culture which Carmen co-founded.

ARCI

The Messina branch of the Italian Cultural and Recreational Association (ARCI) was founded by Carmen Cordaro and Patrizia Maiorana in 2000. Its principal focus is to promote and aid the integration of newly arrived migrants into Italian society as functional, emancipated and self-sufficient individuals. It provides Italian courses, translation services and general assistance with immigration documentation and asylum applications to migrants living in Messina, Sicily.

Our work focuses on helping migrants build a new, honest life in Italy. We help people apply for humanitarian protection documents with the Italian asylum Commission, which every migrant in Italy must do upon arrival. We help the migrants most in need, like those to whom the Commission has refused asylum or humanitarian protection. Most migrants here who aren’t followed by a lawyer or tutor have trouble explaining why they had to leave their country, which could jeopardize their entire application. We help them reconstruct and structure their story so that they can present a strong argument to the court. As a cultural mediator, I translate for those who can’t speak Italian, namely Africans who speak French or English. I speak three Cameroonian languages and four European ones: Douala, Bamiléké and Ewondo, Italian, French, English, and even some Spanish. I also often accompany migrants to the police station to complete their documents or obtain their residence permit.

Fidèle Deholo (19) assists Marc (61), a migrant from Nigeria, at a local post office to forward the renewal application for his temporary residency to Rome. As a volunteer cultural mediator for ARCI in Messina, Fidèle frequently provides translation services and general assistance for migrants in looking to apply for or renew the immigration documents that allow them to legally reside in the country.

Patrizia is the President and other co-founder of ARCI Thomas Sankara. Since we work together, I spend a lot of time with her. Carmen and Patricia are the people I care most about because they guided me and fought for my integration in Italy. They’ve helped me obtain my documents. They’ve helped me prepare for exams. They routinely find me small jobs left and right to earn extra money. Thanks to them, I never lack anything, and thanks to their advice, I’ve learned how to live here. They treat me like their son. They’re family to me.

I also teach some computer science basics to a friend from Sierra Leone. I pass on what little knowledge I have, and the more I teach him, the more I learn myself. I show him how to use a computer, and through him, I learn new things.

Fidèle Deholo (19) teaches computer science to Ibraheem Ba, a fellow resident at the Grand Liberty Hotel and migrant from Sierra Leone, at the ARCI Thomas Sankara library and computer room, in Messina, Sicily.

I finished the mandatory studies that were part of my integration process, Terza Media (8th grade). This year, I’m taking evening classes to transition to a regular school next year and continue my studies in computer science. After that, if possible, I’d like to go to university and learn how to develop software for computers or applications for mobile phones.

Hopefully, that will allow me to find work, rent an apartment, and eventually bring my mother to Italy. I recognize that I’m a great asset to my family here. I can help them if they run into financial problems or if someone is sick. I’m in a privileged position. I want to bring my mother here because I never showed her enough love throughout my childhood. I didn’t treat her with the love, kindness and respect she deserved. And I’d like to make it up to her.

CHURCH

My family is Catholic, so I went to a parochial school in Cameroon. When I arrived in Italy, I decided to receive my first communion and confirmation, so I enrolled in catechism classes. So far, the Catholic community here has genuinely welcomed me and padre Giò, the parish priest, has been very nice to me; he’s always cheerful, charismatic, funny and friendly.

When I was young, I never helped others. In fact, I think my recklessness may have even hurt others. That’s why I’ve decided to change, to help those in need. Now that I’m starting a new life, I want to help those who haven’t had the opportunities I’ve had. To this day, I have people who support me, guide me. Many aren’t so lucky. That’s why I have to help them.

THE GRAND LIBERTY HOTEL

I live at the Grand Liberty reception centre, here in Messina. It’s a former hotel that was converted to accommodate incoming migrants. It was split into two sections: one is for minors and the other for adults. When I first arrived in Messina, I lived in the former, and when I turned 18, I was transferred to the latter.

Fidèle Deholo (19) enters the Hotel Grand Liberty CAS (migrant First Reception Centre), where he has lived since his arrival in Messina in 2017. The Grand Liberty housed hundreds of migrants as they awaited their immigration documentation and humanitarian protection until its closure in late 2019.

Some centres make particular efforts to help their residents integrate; they’ll offer courses in plumbing, electronics, mechanics or other specialties. But less than 20% of centres in Italy do this. Many migrants want to learn and go to school but can’t afford it and have no one to turn to for help.

The problem at the Grand Liberty is integration; the only classes offered here are basic Italian language courses, but other than that, there’s no real infrastructure for learning or professional integration. This is because the Liberty is a First Arrival Reception Centre (called CAS) that is only supposed to house migrants for three months before transferring them to a Secondary (longer-term) Reception Centre – called a SPRAR. SPRARs are meant to facilitate the social and professional integration of the migrants residing there. Their residents are mentored, guided, and offered specialized education, training and work placements. But the Liberty doesn’t offer this because it’s a CAS, not a SPRAR. What’s worse, because the asylum system is so backed up, many- like me – end up staying more than a year here.

Fidèle Deholo (19) studies algebra in a room at the Hotel Grand Liberty First Reception Centre where he has lived since late 2017. In less than two years, Fidèle has become fluent in Italian (in addition to the French, English and Cameroonian languages and dialects that he spoke prior to his journey) and has obtained a middle-school degree that has allowed him to pursue a technical specialization in computer science.

This isn’t to say that the Grand Liberty’s staff aren’t doing their best. It’s still one of the best First Reception Centres in the region, and all its residents know how much the people working here care for them. Filippo, the CAS director, always insists on giving us pocket money and making sure all are warmly clothed for the winter. These are people that I respect enormously and who have helped me integrate into the local community. I can’t explain how much I feel indebted them.

INTEGRATION

When you enter Italy as a minor, you’re entitled to a tutor until the age of 18. But the problem is that as an adult, there’s no one to guide you, help you, or help you understand the way of life. To integrate here, we have to learn how society works. A young person who has just turned 18, who has been denied asylum by the Commission and whom no one follows can easily end up on the streets and do stupid things simply because he has no one to turn to.

Without any assistance, it’s complicated for a migrant to integrate. It’s difficult for Blacks to make Italian friends in Messina. A migrant can spend years here without making a single local friend, someone who can help them, someone to talk to, someone to call when in need. And all of this is symptomatic of a widespread, systemic integration problem.

That being said, some juvenile reception centres have an excellent integration system. I have several friends who are now pastry chefs or work in the hotel business because their centres enabled them to realize their dreams.

I think I’ve integrated well into Italian society: I go to school, I have friends, I have people who care for me, who do everything they can to help me. It’s not the way I imagined when I arrived, but I think I’ve managed to fit in. However, my integration largely occurred despite the reception system, thanks to people like Filippo, Carmen and Patrizia, who have allowed and encouraged me to pursue opportunities elsewhere.

However, beyond the reception system’s issues with integration, there is an even more fundamental problem for migrants in Italy: the Asylum Commission as such.

THE COMMISSION

A process that hands a migrant’s future is entirely in the hands of a few representatives of the Italian state is completely unfair. I’ve known so many people who have suffered beyond explanation on their way to Italy, only to be denied asylum by the Commission, simply because they failed to clearly express their reasons, stories, and trauma. I didn’t expect this. I didn’t know that I would have to justify why I had left my country when I arrived in Italy, or why I should be let in. I expected to be welcomed and integrated immediately. At the moment, only 2 out of 10 asylum applicants at the Liberty obtain their documents immediately. The rest are either in limbo or rejected with an appeal pending.

Imagine travelling to Europe, living in a reception centre for years and then being told that you won’t receive humanitarian protection because a Commission doesn’t find your story isn’t credible, because it doesn’t fit what they have in mind. Being denied humanitarian protection is extremely demoralizing; many become depressed, drop out of school, languish and isolate themselves at the reception centre. Desperate and lost, they no longer know what to do, which is why some prefer to move on to France with the hope of finding better opportunities there.

An abandoned sub-section of Messina’s 17th-century fortress where homeless migrants took shelter during the peak of the 2014-2017 crisis where nearly 500,000 people crossed the Mediterranean to reach Italy. The cave still contains clothes, pots and trash left behind by migrants as they departed for continental Europe.

Without papers, it’s nearly impossible for a migrant to build a life for themselves in Italy. In order to work or go to school, you at least need a residence permit. And if caught undocumented by the authorities, migrants are extremely vulnerable to repatriation. It’s this uncertainty that drives so many Africans to live as a shadow population in Europe and even commit crimes.

I can’t even imagine being deported. I could never take the journey to Europe again. I’d rather die than go back to my country. I’ve been through enough. It would mean that I suffered, struggled, survived all of this for nothing, that I lost all this time. I left my country five years ago with the hope of a better future. I would rather kill myself than go back to Cameroon. I could never cross the Sahara, Libya and the Mediterranean a second time.

BLACK IN MESSINA

Being a migrant in Messina is particularly difficult. In Palermo, Catania, Syracusa, Fondachelli, or other coastal cities in Sicily, it’s much easier for migrants to integrate; African workers are everywhere, there: in restaurants, in resorts, in supermarkets. Some own garages, shops, cars. In Messina, there are only three or four African businesses, Black people are rarely seen driving cars, and it’s rare to see an African working at a local business. Sometimes they can be found in the kitchens of some restaurants, but rarely front of house. In supermarkets, you’ll never see any. In my opinion, Messina still has a long way to go.

Fidèle Deholo (19) buys groceries near his residence at the Hotel Grand Liberty First Reception Centre. Messina, Italy in April 2019.

I’ve experienced a few racist incidents over the years. It used to hurt a lot. Sometimes, when I’m walking down the street and someone sees me coming in their direction, they’ll cross the street to avoid me. When someone is speaking on their phone and sees me, they’ll hang up and hide it in their pocket. Or when someone is heading to their car and sees me coming, they’ll run to reach the door. Many people see us as thugs, thieves, or rapists.

Anti-migrant graffiti in Messina, Sicily, in April 2019. Roughly translated: “Death to blacks"

Once, I was looking for work when a business owner told me, “Vattene nel tuo paese. Qua non c è lavoro. Torna nel tuo paese, Africano sporco” (“Go back to your country. There’s no work for you here. Go back to your country, you dirty African”.) On the bus or the tram, few Messinese agree to sit next to an African. When there’s an empty seat next to me, most would rather stand than sit. That’s why I prefer to take the tram standing up; to avoid these kinds of situations. I see this every day on my way to school.

Often, young Messinese – mostly between the ages of 16 and 25 – shout slurs or insults at me: “Africano! Torna nel tuo paese sporco. Fai schifo” (“Hey African! Go back to your filthy country. You’re disgusting”.) They’ll often shout “schifo” (“disgusting”) as they ride past me on their motorcycles. This hasn’t just happened to me once or twice; it happens all the time.

Remnants of racist graffiti on the wall of a reception centre for underage migrants in Messina, Sicily.

Despite attempts to erase it, the word negro can still be seen.

Sometimes people will try to intimidate us in other ways. Recently someone spray-painted a swastika, “death to all migrants” and “Forza Salvini” next to a juvenile reception center. One night, a group splashed the Liberty’s entire facade with red paint and pummeled the front doors with stones. All of this is to intimidate us.

During the night of August 28, 2018, The CAS Hotel Grand Liberty in Messina was defaced by a group of anti-migrant vigilantes.

Red paint and scuff marks from stones are still visible on the front doors.

At first, this kind of behaviour used to hurt me, but I've gotten used to it.

To be honest, it’s almost become a routine. I don’t have much of a choice. This is the life migrants face here in Italy. We can only accept it. Though if I think about it too much, it still makes me sad.

Racist, anti-migrant rhetoric has recently surged in Italy. The former Italian Deputy Prime Minister Matteo Salvini was a right-wing extremist. As a prominent political figure, his xenophobic remarks and anti-migrant policies gave all racists an excuse to express themselves as they wanted.

As a result, many people now perceive immigration as one of Italy’s central problems. But this logic ignores that Italy’s most significant challenges are nothing new; poverty and unemployment existed long before migration to Italy; organized crime like the mafia is a distinctly Italian phenomenon; theft, drugs and crime have long been a problem. But Salvini’s disinformation campaign has blamed all these problems on immigration. It’s a disgrace.

THE FUTURE

Given all the current problems in Africa, I don’t believe that African migration to Europe will stop. Italy isn’t the only gateway to Europe; people also enter through Spain, the Balkans and Greece. Many seek asylum in Israel. It’s not as simple as patrolling borders and making life difficult for migrants in Europe. Without peace and stability in Africa, migration flows will never stop.

When we look at modern history, Europe is significantly responsible for many of the problems that plague African nations to this day: wars, divisions, poverty, exploitation and suffering. If Europe hadn’t intervened and destabilized the entire continent, most Africans would never want to leave their home countries. Europe colonized us and continues to manipulate and exploit us, and European countries should take responsibility for the consequences.

Italy recently closed its ports to rescue vessels to discourage migrant crossings. Salvini decreed that no boat with migrants on board could disembark in Italy, but crossings continued. The pace and number of arrivals may have decreased, but migrants will continue to come.

If Europe genuinely wanted to slow down migration flows, the first step would be to invest in bringing peace and stability to Africa; the second would be to stop exploiting African resources through corrupt practices and ensure that Africans can actually benefit from their countries’ natural wealth. If this were the case, we would not risk dying at sea to reach Europe.

We find ourselves forced to accept any work that is offered to us. Many Italians say that we’re stealing their jobs, but there’s a lot of work here that they won’t do themselves. And yet, when we agree to do it, we’re called thieves. How is this fair?

Life as a migrant in Italy isn’t easy. The reality here is far from the Europe we imagined; it’s not what we saw on television when we were in Africa. Our media only show the best of Europe, not the suffering we can experience there. That’s why so many Africans come here; they don’t understand the difficulties that they’ll face here. And here in Europe, it’s bizarrely the opposite; the media never seem to speak well of Africa; they never show the positive or the beautiful, only instability, suffering and precarity.

I don’t know where life will take me tomorrow. I don’t know if I’m going to settle in Italy or I’ll move on elsewhere. Only time will tell.

What I do know is that if I hadn’t joined ARCI Thomas Sankara, if I didn’t have such a strong network of people that care for me and support me, I might be in Germany or France right now. Even if racist sentiment is on the rise in Italy, it doesn’t mean that all Italians believe in it. I’ve had the fortune of meeting so many good people, Italians who want me the best for me, who even love me.

Since I left Cameroon, many people have helped me, on the road and here in Italy. Thanks to them, I avoided a lot of suffering. Thanks to them, I’m here today. And it’s because of their help that I want to give back to those who need it.