Abdirahman's story

My name is Abdirahman Abdulahi Hasan.

I was born in Afgoye, Somalia, in 2001. I’m not sure of the exact date since those aren’t recorded on birth certificates in Somalia. All I know is that I’m 18 years old.

follow Abdirahman's Journey

click hereHOME

Editor’s note: The following story is based on conversations with Abdirahman from March 2019. It reflects his views and life at the time, much of which has changed since. The text was edited and collaboratively re-written for clarity with his complete involvement and approval. Most importantly, this remains his story, told in his words.

Afgoye is a village about 30 km from Mogadishu, the capital of Somalia. It’s a fertile place with a river running through it, where most people work in agriculture, fishing or manufacturing, alongside nomadic clans like the Rahaweyn and Hawiye.

When I was around two years old, a group of men attacked our home. They killed my stepfather, raped my mother and killed my two baby sisters. They were twins, not even a year old.

When I was around two years old, a group of men attacked our home. They killed my stepfather, raped my mother and killed my two baby sisters. They were twins, not even a year old.

After that, my mother disappeared. We only recently found each other again. She told me that she feared for her life, so she fled to Saudi Arabia and briefly returned to Somalia before moving to Indonesia. We video chat from time to time.

Our neighbours found me after the attack, took me in as one of their own, cared for me and raised me. I went to school with their children, and we studied together. When I was old enough, they told me what had happened to my family. They even kept photos of my mother for me.

But I grew restless, and we began to argue. When I turned eight or nine years old, I ran away to Mogadishu.

MOGADISHU, Somalia

Our country was and is at war, so life was hard. As a child, I saw death all around me. I lived alone on the streets for a while, sleeping where I could, living hand to mouth, doing whatever I could to earn money – mostly cleaning shoes.

Eventually, I found somewhere to stay to sleep, an abandoned building in Bondhere district. There were many bad people there, violent people, drinking and smoking. I wasn’t the only child, either. It was a terrible life, without access to healthcare or education or even water to bathe.

In Somalia, chaos, violence and death are everywhere. It's senseless; no one is safe; people die, good and bad.

I had nothing. I didn’t have a home or an education. I didn’t have anyone who cared for me; I didn’t have a family, I didn’t have anyone to support me. I had no one to make me happy, to make me laugh.

I didn't have the time or energy to think of the future, only how to survive in the present. I was just waiting to die [...] Sometimes, I even prayed for it.

Sometimes, I would see children my age laughing and playing with families who cared for them. And then I would think about how I had no one.

I found kind people, though. When I was 14, mister Jamal, the headmaster of a private school in Mogadishu, offered to cover my tuition. For the first time in years, I was able to study. The school even allowed me to eat for free, so I was never hungry. I’ll always remember mister Jamal. He’s one of the few people who supported and cared for me. It’s thanks to him that I learned English.

For the first time, I began to think about my future. I realized that I couldn’t go on in Somalia; I needed to find somewhere safe to study and develop myself.

At the time, I wasn’t thinking of going to Europe or Italy yet, just elsewhere in Africa.

I reached the border near Dolow by bus and crossed into Ethiopia by foot.

JOURNEY

It was an anxious crossing. In Somalia, children in the countryside – some as young as nine – are often kidnapped by terrorist groups like Al-Shabaab or Al Qaeda. They’ll take them, train them and force them to fight. They give them Kalashnikovs or bombs and train them as soldiers and suicide bombers. They rarely venture into Ethiopia, though, since they fear its central government and army. I was lucky I didn’t encounter them.

ADDIS ABABA, Ethiopia

I spent six months in Addis Ababa. After three months, I found work at a restaurant in Bole Michael district. For the first time, I earned enough to take care of myself; I had somewhere to sleep, could afford to eat and bathe, even save money.

But Ethiopia wasn’t an easy place to live, either. Somalia was my homeland. If I had nowhere to go, I could always sleep on the streets or outside. Addis Ababa’s streets were much more dangerous, as armed gangs frequently rob and kill people, even fighting the police. I didn’t feel much safer there than I had been in Somalia, so I decided to move onto Sudan.

I took the bus, first to Bahir Dar, and then through the border at Metema.

SUDAN

It’s in Sudan that I first met people travelling to Europe. They explained the route to me; first, crossing the desert into Libya and then crossing the sea to reach Italy. So I found a smuggler there.

In Sudan I quickly passed through Khartoum before moving north, onto Batn-El-Hajar, a town along the Nile. I waited there for a month as the smugglers gathered a big enough group of migrants to send to Libya, around 300 people. We were from all over the horn of Africa: mostly from Somalia, Eritrea, Ethiopia, and Sudan.

The smuggling network is spread across Ethiopia, Sudan, and Libya. Different smugglers cover different parts of the route; they’ll transport a group of migrants to a given relay point where they’ll hand over the migrants to the next driver, and so on. The smugglers gather people into groups of 50 to 100 and pack them into entire caravans of pickup trucks. Since the journey is dangerous, no one pays upfront; it’s only when reaching Libya that relatives or friends wire money to the smugglers.

One night, they packed us into the back of their trucks, and we departed for the desert.

To hide us from passersby and authorities, they would make us lie down on top of each other, like rows of logs, and cover us with a tarp. Combined with the desert sun, it felt as if we were in an oven; unbearably hot and difficult to breathe. We weren’t allowed to talk, or move or stick our heads out for air, so we tried to sleep. If we made any noise, the smugglers would beat us mercilessly, even threaten to kill us.

We ran out of food and water after five days. Our truck broke down, which took two days to repair. Meanwhile, people became thirsty, hungry, weak and sick. For ten days, we didn’t eat or drink. People started dying.

Our journey lasted 15 days. By the time we entered Libya, 15 people had died.

It was 2017, and I was 16 years old.

LIBYA

We crossed into Libya at a place called Bohar. The smugglers then brought us to a prison in the middle of the mountains, in Beni Walid, to hold and ransom us to our families.

When they realized that I had no family or way to pay them, they tortured me. They tied my hands and feet and would burn me with hot irons or by melting plastic all over my body. When I would fall to the ground, they would kick me in the head. They even shot me.

And I wasn’t the only one. Anyone who wouldn’t obey or wouldn’t pay the smugglers, they tortured. “Pay the money. Pay the money. Pay.” they would tell us. They would beat us every day, morning, afternoon, and evening.

I never knew such cruelty was possible. It was inhuman. They would treat us as if we were nothing. Sometimes, I would ask myself: “Am I man or beast?” Sometimes, to escape the pain, I would separate my mind from my body. I would try to think of another place and send my mind there.

These jailors were heartless. They beat us mercilessly and would kill people on a whim. I still don’t understand why they were so cruel. I thought that I would never leave, that I would die there.

I spent two years there.

Abdirahman shows the scars he received while detained by smugglers in Libya for two years between 2015 and 2017.

They tied my hands and feet and would burn me with hot irons or by melting plastic all over my body. When I would fall to the ground, they would kick me in the head. They even shot me.

I had grown used to a harsh life in Somalia. There’s no such thing as human rights or protection there. I had seen men suffer and die. I had seen women and children abused.

The journey across the Sahara was brutal, but it wasn’t unlike the life I had experienced thus far. What I encountered in Libya, though, I can never forget.

The living conditions in prison were atrocious. They would barely feed us; our daily meals consisted of a bit of pasta and water.

We slept hundreds to a room, living in large, dark, underground cells filled with mosquitos and rodents that would devour our bodies. We rarely saw the sun, being almost always underground. The floor was earthen, and we couldn’t bathe, so we were always dirty.

Hope died in that place.

One day, after about 15 months, they gathered all those who hadn’t paid into the courtyard, around 300 to 350 poor Eritreans, Somalis, and Sudanese. I was supposed to be among them, but I snuck away and hid in a nearby toilet with a small window that gave onto the courtyard. I saw the guards line them up and slaughter them. When they were finished, they dragged all the bodies to a long trench outside – a mass grave – and hosed away the blood from the courtyard. I returned to the large and now empty cell, where the guards found me, alone. They were confused as to how I had survived but decided to let me live.

Sometimes, I have flashbacks or dreams about that day. Bad dreams. I don’t think those will ever go away.

After nearly two years of constant abuse, mistreatment and malnutrition, I had become anemic. I was weak and had lost a terrible amount of weight; rail-thin, I could barely move and needed constant assistance to do even the smallest of things. The guards eventually felt sorry for me and decided to release me along with a group of migrants headed for the sea.

THE CROSSING

I was so weak that I could barely move. Others had to carry me. “Just leave me,” I kept telling them, until I fainted from the pain. I’m not sure how we made it to Tripoli, but at around 2 a.m., as I lay unconscious, 300 of us boarded an inflatable boat bound for Italy.

I drifted in and out of consciousness during the crossing, so I only remember brief flashes. I remember being placed in the centre of the boat, with people sitting all around me, some even on top of me. I couldn’t see the water, only bodies and the sky. I could barely breathe. I was convinced that death was near.

I couldn't see the water, only bodies and the sky.

Suddenly, I woke up as foreigners were transporting me onto a rescue ship. I was surprised and confused. The doctors onboard treated me until we reached Italy, where an ambulance brought me to a hospital.

ITALY

In Africa, we think that reaching Europe will solve all our problems; we imagine that we'll easily find work and make money. But once you arrive, you realize that it isn't so. Life is complicated here. Life is hard.

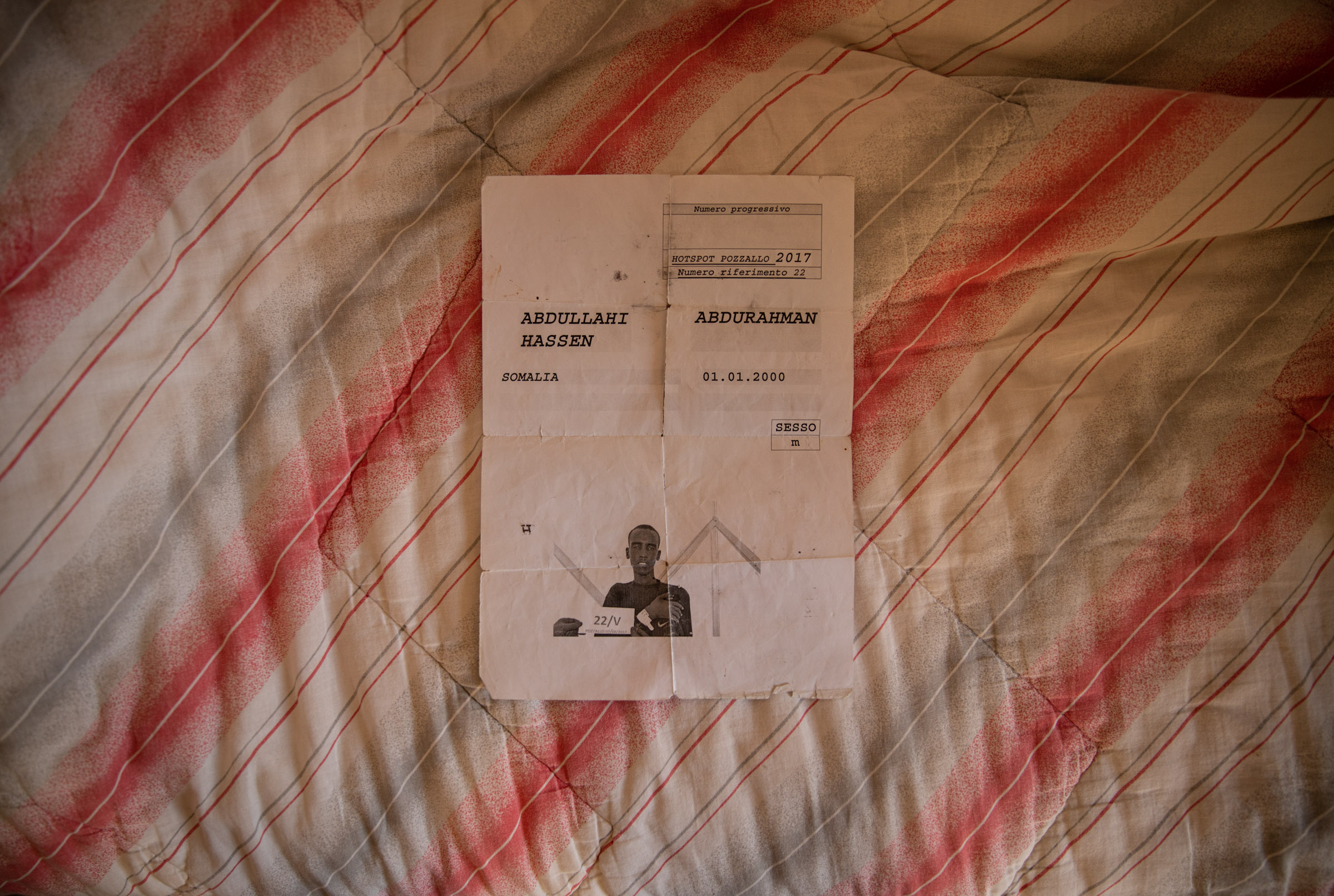

The "Hotspot" of Pozzallo is where Abdirahman first arrived in Italy after being rescued at sea, located in one of the Island of Sicily's southernmost ports.

Located in one of Sicily's southernmost ports, the "Hotspot" is a federally run first-arrival center where migrants are treated, identified, and processed upon disembarking in Italy.

It’s been difficult to adapt. Life here is so different from Somalia. There are many privileges here: peace, stability, education, human rights. There are organizations here that help migrants integrate and build their lives. There’s a democratic government that assists and cares for its citizens. These are all great things, but not all opportunities are easily afforded to migrants.

We arrive knowing nothing about this country, so we need help understanding the way of life here, how to behave and how society works. When we arrive, we’re told that we’re “safe, now,” that we have rights, here, that we’ll get everything we need. “Don’t worry. Things are different here”. But later, as you begin to understand how everything works, you realize how complicated life can be in Italy. Sometimes, it can feel unfair.

LIFE AT THE SPRAR

It can be challenging for so many people from different countries – each with their own culture and mindset – to live in a small reception center together.

Some are from Asia, but most of us are from all over Africa, each with our own habits, language and culture. Senegal and Somalia, for example, are nothing alike. Just because we’re from the same continent doesn’t mean that we have anything else in common. These differences in such close quarters can cause friction or conflict, arguments and fights.

Just because we're from the same continent doesn't mean that we have anything else in common.

There are also many rules to follow in order to live here. If the staff tells you to do something, you don’t have much of a choice if you want to stay. I don’t mind being told what to do if it’s for the good of all. That’s not a problem. But I find myself frustrated with certain situations, even belittled, sometimes. I’m just a guest here. I want a home.

I generally get along with the others at the SPRAR; we greet each other politely, chat a little, then we leave and pursue our interests. But there’s not much of a relationship beyond those interactions. After everything I’ve experienced, I find it difficult to trust people.

My closest friend here is Anna, my social worker and psychologist. She’s given so much to me, protecting and supporting me through all my challenges and problems. I share anything with her, my secrets and burdens, whether severe or lighthearted, happy or sad. Very few people have been so kind to me here. I feel like I know her, and she knows me. I trust her. She’s like a sister to me.

She’ll often call just to see how I’m doing. “Abdirahman, how are you? How are things? What are you doing? How was your day? How is your health?” I can tell that she sincerely cares about me.

ASYLUM

I was granted five-year humanitarian protection by the Commission, called subsidiary protection. Although it’s a better result than most applicants, I’m disappointed that I wasn’t granted asylum, given what I experienced in Somalia and Libya.

There are often complications in processing our asylum applications or receiving our documentation; sometimes, the asylum commission will refuse to process our applications for minor clerical reasons; other times, they’ll make mistakes that delay their response.

The original identification document that Abdirahman received upon arrival at the Port of Pozzallo's "Hotspot" in 2017. In the photograph, taken shortly before he was brought to a hospital, he struggles to stay conscious.

Without documents, we can't do anything: we can't work, we can't rent an apartment, we can't rebuild our lives here.

Meanwhile, we remain in Limbo. They’ll tell us that they’re “working on it,” that they don’t work for us and that we just have to be patient. But we can’t always afford to wait.

Italy is a free country, but without documents, it’s as if we don’t exist. We can’t work or rent an apartment. It’s not right.

INTEGRATION

Sicily is different from the rest of Europe; it’s quite poor in places and can be extremely difficult for even educated locals to find work, let alone migrants. If they struggle to find work, what hope do we migrants have?

Many Italians believe awful things about us that are written in the press; they think we’re dishonest, or stupid, or dangerous, or leeches. They say that we take work from them. They blame us for their problems. But it’s the same as anywhere in the world; there are good and bad people everywhere.

I’ll feel free when I can live an independent and stable life: studying and working, respecting others. I just need opportunities to develop myself.

Although I haven’t found those opportunities yet, I hope to in the future.

POSSIBLE FUTURES

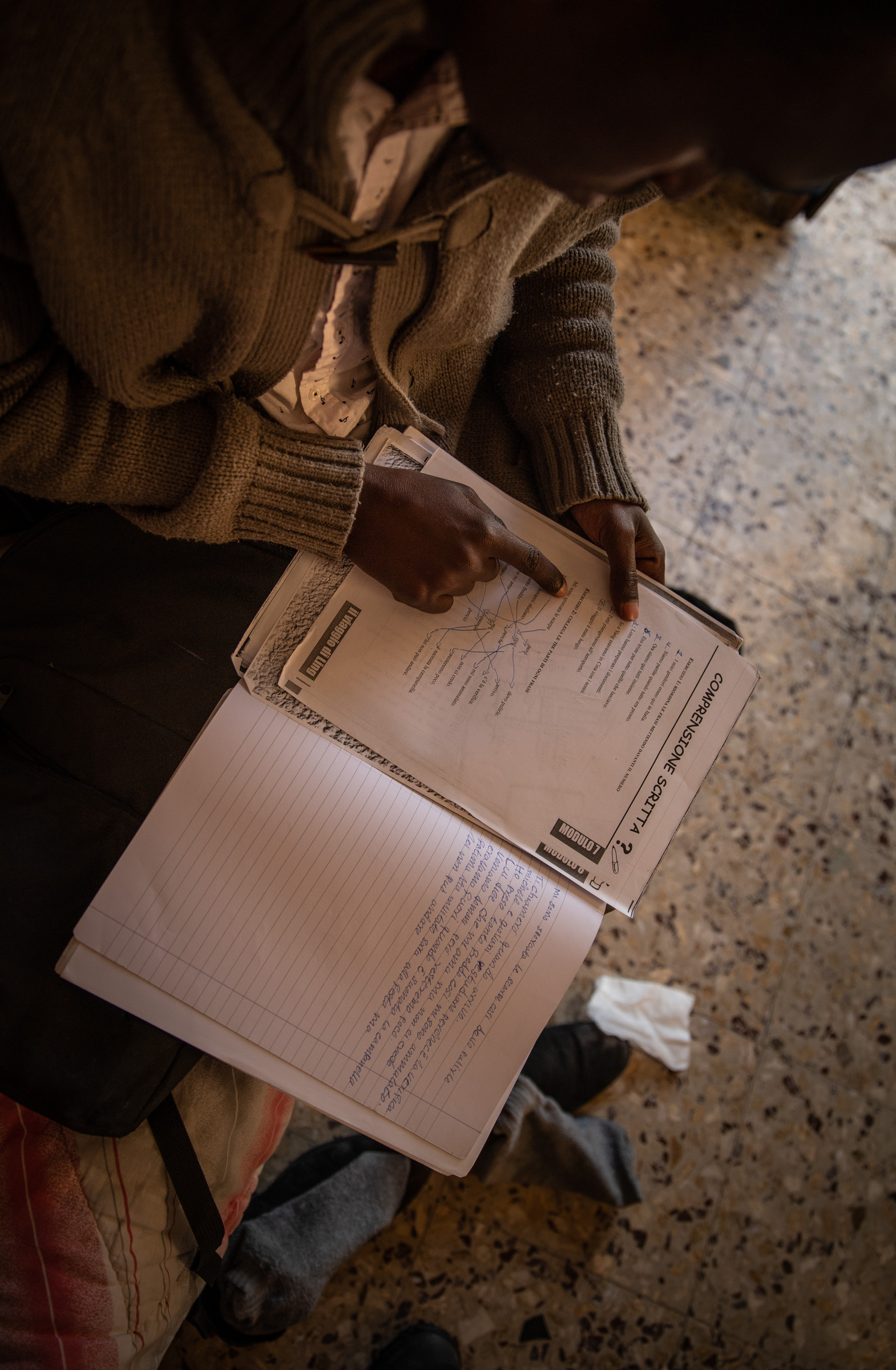

In the morning, I study, eat and go to school for my morning classes. Then, I return to the reception center for lunch, as it's not far, and go to school for my afternoon classes. Then, in the evening, I'll come back, cook for myself, study or read some more and go to sleep.

I left my country in search of opportunity, and mainly to study.

I’m not interested in money or becoming rich. I’m interested in acquiring knowledge, bettering myself, my life and the lives of others. I’m not looking to go elsewhere in Europe; I want to stay and become an Italian citizen. I want to study here and build a life.

But given the constant political instability surrounding the status of migrants in Europe, I always have this fear in the back of my mind, the fear that one day, the government will decide that they don’t want me anymore and send me back to Somalia. And I can’t do that. I can’t go back. It’s too dangerous. There’s no future for me there.

I love my motherland, but at the moment, it’s impossible to live there. It’s too unstable. Nobody listens to each other. There’s no rationale for the civil war tearing the country apart. Bombs go off every day. People die every day. I’m lucky to have reached Europe; I have rights here, protection, education, free healthcare. I would have none of that in Somalia.

There is so much suffering there; our children lack education, healthcare, or a decent quality of life.

We deserve peace, equality, safety and stability as much as any other country.

Somalia is a wealthy nation; it has so many resources like oil and gas, gold and diamonds, fishing and agriculture. We have the longest coastline in mainland Africa, which holds tremendous potential. If Somalia were to find peace and stability, I’m sure that many countries around the world would flock to invest there. Somalia is a massive opportunity for the international community, but it needs help. It needs military support to bring the civil war that has been ravaging it for decades to an end, and it needs economic support to stabilize and rebuild itself so that it can extract and manage its resources.

But above all, the international community needs to respect Somalia’s sovereignty and interests, our people and our territory. We suffered much under colonialism, when Britain, France and Italy divided the country piecemeal a hundred years ago, not to mention after the disastrous American military intervention in the 1990s.

Hopefully, once I have finished my studies, built a good life for myself here and developed myself as a person – in 20 or 30 years – I can go back and help the Somali people.

Abdirahman completes his written comprehension homework in his bedroom at the SPRAR. Having had limited access to education while growing up homeless on the streets of Mogadishu, studying amd improving his language skills is a priority.

I have back problems, so I can’t perform manual labour like most people at the SPRAR. They work in campagna, as seasonal workers picking tomatoes, oranges, or whatever crop needs picking.

If possible, I’d like to become a cultural mediator for newly arrived migrants. I had to learn Arabic to get by in Sudan and Libya. And since I came to Italy, I’ve been studying Italian. I’m still learning, but I’m improving every day, and I understand most of what is said to me. I’m also working on my English by reading and watching videos. So in all, I speak Somali, English, Italian and a little Arabic, which could be useful.

I know that many people need help. I've been there myself.

I experienced so many setbacks, faced so many challenges, and saw so many horrors in my life. But ultimately, these made me into the strong, driven and patient man that I am today. A journey like mine reveals who you are. I know what it’s like to be homeless, to suffer, to lose hope. I know that many men, women, and children have experienced the same things as I and need support here in Italy.

A mediator not only needs to interpret and translate but be kind and honest with people.

That’s something I can see myself doing. It’s honest work.

!["I never knew such cruelty was possible. It was inhuman. [...] Sometimes, I would ask myself: "Am I man or beast?" To escape the pain, I would separate my mind from my body".<br />

<br />](https://migrantsea.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Abdirahman-Scars060GreenDSC04240.jpg)